< Return to Contents | Previous I Next >

People saw poor mental health and addiction as symptoms of poverty, social exclusion, trauma and disconnection. They talked about threats to basic needs such as affordable and safe housing, quality education, meaningful employment, adequate income, social connectedness, freedom from violence and reliable social support. They explained how this leads to chronic stress on families, whānau and individuals and compromises wellbeing.

Many people called for a mental health lens to be applied to all policies that shape society (for example, education, criminal justice, economics, care of the elderly and housing policies) and argued for prevention to reduce risk factors, such as alcohol and other drug abuse, homelessness and violence, that harm the wellbeing of individuals and communities.

People placed particular emphasis on reducing economic deprivation among our children, mokopuna and young people, as child poverty paves the way for worse health outcomes in childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Young people identified insecure employment, spiralling housing costs and the burden of debt as major sources of anxiety. Similar social and economic issues were raised by under-served or marginalised groups such as the elderly, disabled people, homeless people, Rainbow communities, refugees, migrants and people living on long-term income support.

We repeatedly heard how poor mental health outcomes can become endemic within communities. We met leaders in communities devastated by the impact of easy access to alcohol and other drugs. People told us how whole communities, not just individuals, can become depressed or anxious, disconnect from each other, and lose the sense of trust and the ability to work together. They expressed dismay at their limited influence over important decisions that affect community wellbeing, such as the number and placement of liquor or gambling outlets and access to addiction detoxification (detox) facilities. They wanted access to national resources to create local solutions and sought wider powers to take charge of what they perceived to be the main drivers of poor mental health outcomes for their communities.

Numerous submissions described the impact of discrimination on the basis of mental health status – how it added to their mental distress and sense of alienation. Discrimination was reported to still be common in New Zealand society and within the mental health system. We also heard about the harmful effects of discrimination on the basis of ethnicity, culture, disability and gender identity. Rainbow youth and other marginalised groups reported not feeling safe accessing mainstream services and suffering harm from discrimination.

People talked about loneliness and isolation in our communities. They spoke of the need for stronger connections and manaakitanga, practical care and concern for the wellbeing of others.

We were told that the pressure to be constantly available for work fosters anxiety, insecurity and isolation.

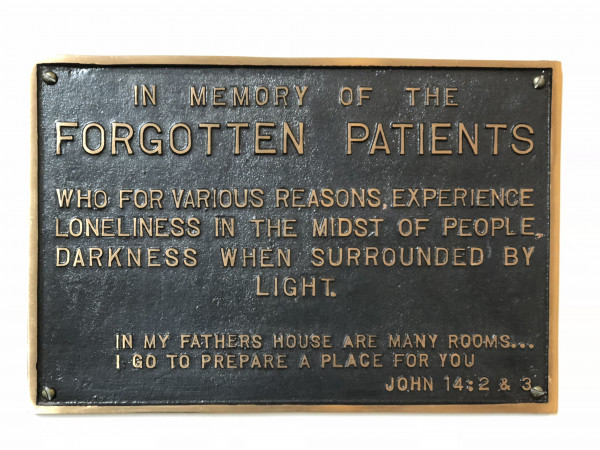

We were reminded of the forgotten patients in our system.

|

|

Photo: Karakia i te koroha, Prayer in the Wilderness, Chapel at Kenepuru Hospital, Porirua |

Many submissions highlighted trauma in childhood as the origin of mental distress and the trigger for counterproductive coping mechanisms such as addiction. People noted that steps to prevent or reduce the trauma of childhood abuse and neglect, sexual abuse and sexual violence, adult partner violence and bullying at school and work should be recognised as strategies for preventing future distress and investing in the wellbeing of future generations.

We were told that health services responding to mental distress need to get better at acknowledging and responding to the trauma that underpins ‘symptoms’, rather than merely offering ways to ‘dull the pain’. People noted that state agencies such as Oranga Tamariki— Ministry for Children, schools, New Zealand Police, the Department of Corrections, Work and Income New Zealand and mental health services can cause or exacerbate trauma.

A repeated theme was that intergenerational trauma can affect families and whānau and that understanding mental health through the lens of trauma requires a change in mindset and different approaches to healing for individuals, families and whānau.

People demanded action to reduce the harmful effects of drugs (especially methamphetamine or ‘P’) and alcohol, particularly among young people and during pregnancy. We heard from communities being torn apart by the P epidemic. Many people expressed concern about the ease of access to alcohol and gambling in our communities, noting their potential for social harm if not tightly controlled. They talked of our national ‘love affair’ with alcohol, how alcohol use fuelled their depression and suicidal thoughts or triggered violence and neglect of children. They called for decisive action limiting the sale and promotion of alcohol, particularly around children and young people (including sports sponsorship).

Gambling was also seen as harmful due to its addictive nature and the financial stress and anxiety it causes families, contributing to neglect of children and family violence.

< Return to Contents | Previous I Next >

Last modified: